Do you remember what it was like to first learn the body of knowledge which ultimately became your profession? So much of that initial learning is totally second-nature to us now, and we don’t even think about the fact that there was a time when we didn’t know it. We may have even forgotten how much we struggled to learn what seems trivial to us now. I suggest we need to have some empathy for our students' struggles.

Stay with me, while I relate a personal story to you. I’ll come back to empathy in a bit.

My wife and I have traveled to England, Scotland, and Ireland a few times, and thoroughly enjoyed each for many different reasons. Aside from the normal logistical challenges that arise, we found the trips and conversing with the locals rather easy. Obviously, the primary language spoken in England is English (although some of the words do have different meanings), but even in Scotland and Ireland, it is easier to converse in English than you might think.

|

| Bayeux, France |

Last summer we ventured off of the islands onto the continent for our first time, traveling to parts of France and Germany for two weeks. Neither my wife or I speak French or German. We were assured by friends that—at least in the larger cities—this would not be a problem for us, and mostly that was true.

|

| View from our apartment in Bayeux, France |

We started our visit to France in

Bayeux, an old small town in Normandy on the northwestern coast. It is largely a tourist town, with a major attraction being visits to the various

D-day and Normandy landing venues in the surrounding area. We stayed at a great Airbnb apartment in a multi-centuries-old building in the center of town. Being a tourist town, we had very few issues communicating with others. We enjoyed our time there and would have liked to have stayed a couple more days, but alas we had other reservations in Paris.

|

| Our apartment in Paris, France |

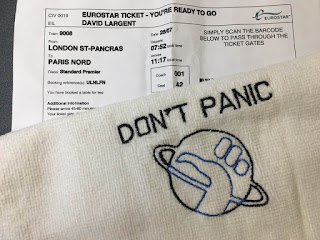

We boarded a train bound for Paris, where we had arranged to stay in another Airbnb apartment. This one was in Northeast Paris, far out into the residential suburbs. This was definitely not an area which catered to tourists, but it was wonderful to see this part of Paris as well. The apartment was great (complete with a washing machine, but no dryer), and was conveniently located just a few blocks from a Metro commuter train stop, which allowed us to get most anywhere we wanted to go. It provided a very cost-effective and pleasant way for us to stay in Paris.

By the time we arrived at the apartment the first evening, it was time for dinner. We also planned to eat our breakfasts in the apartment each morning and make our lunches to take with us each day. With a bit of research via information provided in the apartment by the owners, we figured out that there was a community square a few blocks from the apartment which had a few restaurants, but more importantly, a grocery store. Off we headed on, what seemed to us at the time, a simple mission—get dinner and buy groceries for the week.

|

| Paris, France - Eiffel Tower |

|

| Paris, France - Notre Dame Cathedral |

Now remember, we don’t speak French, and we’re in a residential area of Paris, where it is unusual to have lots of tourists. We hadn’t realized that yet, however. Since arriving in Paris earlier that day, we’d spent the afternoon in the center of Paris, with all the other tourists, and store clerks who spoke English well enough to communicate with us. After walking a few minutes, we arrived at the square, and located a viable take-out restaurant for dinner. We entered and proceeded to try to figure out what we wanted to eat. All of the signage was in French, and the workers didn’t speak English. Did I mention that we don’t speak French? Fortunately, there were pictures, and we eventually got something bought and took it out to sit in the square to eat. We both enjoyed what we had for dinner, but I’m still not sure what it was I ate that night. We were starting to realize we weren’t in Kansas anymore!

Next task: buy groceries. We entered the store and it looked encouragingly familiar; aisles of packaged food on shelves, and lots of fresh, unpackaged food. But again, no English signage, and of course the package labels are all in French. And as a reminder (wait for it…), we don’t speak French. Long story short, what should have been a 10- to 15-minute jaunt into the store to pick up a few breakfast and lunch supplies, along with other miscellaneous items turned into nearly an hour excursion. Google translate quickly became our friend! We successfully bought everything we needed, but it took us way longer than we expected it to. By the end of the week, I was recognizing a lot of French words and understanding what they meant. I was somewhat surprised how often I could make a reasonably correct guess about a French word because of an English word being (somewhat) similar.

I felt a bit isolated after my experience that evening. I realized that if I didn’t know what something meant, I was going to have to ask questions. But if I didn’t know how to, or what questions to ask, how could I do that? I did find that the local residents were very willing to help me understand, as long as I was trying to understand their language and use it when I could. Don’t get me wrong, I thoroughly enjoyed my time in France (and Germany), but this was my first time traveling when communication had been a challenge for me. I was experiencing something new and unfamiliar, and had to work through it.

|

| Paris, France - Painting of "hieroglyphics" on the wall in a Metro commuter train tunnel |

As I reflect on the experience I had that evening, I wonder if it is similar to what our students experience at the start of our introductory courses. They are being immersed in a topic they know little or nothing about. They have little context to which they can attached their new knowledge. We often use new terminology, or use their familiar words in different ways. They may know they have questions, but don’t believe they know enough to ask us questions. As someone who teaches an introductory computer programming course, I’m asking students to learn new concepts and to learn a new (programming) language, complete with its own (unusual) punctuation.

I came back last summer with a renewed appreciation for (some of) what it means to be a new student. We teachers need to remember that we haven’t always known everything we now know. There was a time we struggled to learn it, and that is the same struggle our students are having now. If we are to be effective guides in the learning process of others, we need to remember those first days when we were learning the material which we are now helping others master.

We need to have empathy and remember what it’s like to be in a foreign land and not know the language. How can we reach out and help these intrepid travelers we call students? Share your ideas below.